У даній статті розглядається роль ефекту тестування у довготривалій пам’яті. На сьогодні досить часто у педагогічній та когнітивній психології постає питання навчальної діяльності особистості, її успішності та ефективності. Опираючись на попередні дослідження ми дослідили 4 навчальні стратегії, які при підготовці апріорі використовують студенти. Одна із даних навчальних стратегій включала у себе часте тестування, що передбачає краще запам’ятовування. За проведеним дослідженням було виявлено позитивний та ефективний вплив тестування на навчальну діяльність особистості та на якість її запам’ятовування.

У даній статті розглядається роль ефекту тестування у довготривалій пам’яті. На сьогодні досить часто у педагогічній та когнітивній психології постає питання навчальної діяльності особистості, її успішності та ефективності. Опираючись на попередні дослідження ми дослідили 4 навчальні стратегії, які при підготовці апріорі використовують студенти. Одна із даних навчальних стратегій включала у себе часте тестування, що передбачає краще запам’ятовування. За проведеним дослідженням було виявлено позитивний та ефективний вплив тестування на навчальну діяльність особистості та на якість її запам’ятовування.

Memory is a mental phenomenon of fixing storing, and retrieving the past experience that enables its repeated usage in the further person’s life.

According to the time during which information is kept there distinguish the following kinds of memory:

- sensory memory that lasts 0,2-0,5 seconds and helps the one to orientate oneself in the surroundings;

- short-term memory that provides remembering one-off information for a short period of time, i.e. from a couple of seconds to a minute;

- long-term memory that stores information for a long time;

- working memory that appears while performing specific activity and is essential for its accomplishment at any given period of time.

Thus, we have decided to research influence of testing effect on the long-term memory.

Testing-effect is a researched and independent phenomenon.

The term “testing-effect” referres to the phenomenon of testing one’s memory not only for assessment of what they have already known but also for increasing capacity of further retrieval (Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jefferey D. Karpicke, 2006).

Testing increases capacity of further retrieval more than repeated studying of the material even though a test is given without reverse relation. This phenomenon is also called testing effect, and is studied by psychologists who work in the sphere of cognitive psychology. Today, the attempts to research testing effect have been renewed with new power in order to find out why studying is so effective, and suggest that strategy of testing is to be implemented into the modern system of education (Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jefferey D. Karpicke, 2006).

Nowadays testing and exams are only used to check students’ knowledge. Our research is aimed at proving that not only does testing check knowledge, but it also changes knowledge improving retrieval of the tested material. By testing material we may have better positive effect in future retrieval than by second learning of the same material, even though testing results appear to be far from excellent, and test is given without reverse relation or information is missed.

We believe that the testing-effect has an influence on the long-term memory. If it is uses in teaching, we can have better results. Students knowing that they will have test or check will learn more material. Moreover, testing has effect of training. Use of testing technique by students, teachers, pupils, etc. can train their long-term memory (that possible to designate as aforementioned influence). Also while using testing students will have a setting that it will be necessary to learn a material as they are expected to pass a check and consequently can grasp bigger amount of the material. However this point is not the most important. In comparison with the simple doctrine testing gives the chance not only to remember bigger quantity of material, but also to show good results at the further check (that gives the chance to recollect bigger amount of material at checking after some time).

Also when students use the testing, they have possibility to estimate more precisely and comment on that that they have remembered or have learnt. And in that situation we can talk not only about memory, but also of metamemory. That is why we can talk about influence of the testing effect on a long-term memory when we talk about testing trials. Importance and value of our research entails giving the chance to track a role and presence of influence of testing for long-term memory as well as metamemory. Also it gives the chance to choose from certain quantity of studying strategy one – the most effective.

The actuality of our research lies in of definition of strategy testing is used very seldom though it shows the best results.

The test is used approximately once on the module that is extremely seldom. In an ideal version during studying it will be better to use the testing more often, once a week, for example, that will stimulate students to get the best results.

The idea that testing improves keeping of material is not new. As early as in 1620 F. Bacon wrote: “If you read an extract from a text at least 20 times, you will not learn it as easy as when you read the same text 10 times and everytime try to retell it by referring to the parts of the text which your memory fails to remember’ (F. Bacon, 1620/2000, p.143; Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke, 2006). By this quote F.Bacon highlighted the power of testing effect. In our research we will try to show that this hypothesis is correct and that the testing effect improves retrieval of material.

There exist a great number of experiments designed to research the testing effect. They are based on verbal studying that traditionally uses certain pairs of words (e.g., Hogan & Kintsch, 1971; Izawa, 1967; McDaniel & Masson, 1985; Thompson, Wenger, & Bartling, 1978; Tulving, 1967) or set of pictures (Wheeler & Roediger, 1992) as stimulating material. However, 17 years ago a scientists whose name is Glover made the following conclusion conserning the studied phenomenon: “Testing phenomenon has not passed but is forgotten”.

Gates (1917) and Spritzer (1939) also mentioned strong positive effect of testing on material retrieval. Tulving’s (1967) research results proved as well that testing effect exists, however, Lachman and Laughery (1968) decided to check reliability of these results. Their article asks: “Is a test trial a training trial in free recall learning?”, and then gives the answer “yes” relying on the results of scientists’ own experiment.

In 2006 Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke also decided to check results of research described by Tulving. They used three conditions (standard, repeated study, and repeated test). They used 40 words and a 3-s rate of presentation, so that the accompanying tests lasted 2 min and time on study trials and recall tests remained equated. They examined learning curves and compared the conditions on the fife common test positions out of the total of 20 study and test trials. That is, every 4th trial was a test trial for all three conditions (standard: STST…; repeated-study: SSST…; and repeated test:STTT…), so they could directly compare recall on the 4th, 8th, 12th, 16th, and 20th trials across the three conditions. They also eliminated short-term memory effects that would normally disadvantage the repeated-test condition by using Tulving and Colotla’s (1970) method of separating short-term from long-term memory effects. Accordingly, having finished the experiment and elaborated the results Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke found the phenomenon of testing effect.

Moreover, procedures developed to estimate and remove item-selection effects (when initial test performance differs across conditions) demonstrate that testing facilitates learning even when item-selection effects are present in the data. For example, Modigliani (1976) showed that increasing the delay before an initial test led to increasingly greater effects of testing (Jacoby, 1978; Karpicke & Roediger, 2006a), and when the enhancement effects due to testing were mathematically separated from itemselection effects, the positive effects of delaying the initial test were attributed entirely to enhancement effects, whereas item selection estimates remained invariant across the delays (and were quite negligible to begin with). Other procedures for handling item-selection problems were developed by Lockhart (1975) and Bjork, Hofacker, and Burns (1981) and show similar results. To conclude, the testing effect is not simply a result of additional exposure, or overlearning, or item-selection artifacts.

One explanation for why tests that require production, or recall, of material lead to greater testing effects than tests that involve identification, or recognition, is that recall tests require greater retrieval effort or depth of processing than recognition tests (Bjork, 1975; Gardiner et al., 1973). Bjork (1975) argued that depth of retrieval may operate similarly to depth of processing at encoding (e.g., Craik & Tulving, 1975), and that deep, effortful retrieval may enhance the testing effect. As already discussed, increasing the spacing of an initial test— which can be assumed to increase retrieval effort—promotes better retention (Jacoby, 1978; Karpicke & Roediger, 2006a; Modigliani, 1976), so long as material is still accessible and able to be recalled on the test (Spitzer, 1939) or feedback is provided after the test (Pashler et al., 2003). This positive testing effect probably reflects greater retrieval effort on delayed tests. Other evidence from different sorts of research also leads to the general conclusion that retrieval effort enhances later retention.

Gardiner et al. (1973) asked students general knowledge questions and measured the amount of time it took them to answer the questions. At the end of the session, they gave subjects a final free-recall test on the answers. The longer it took subjects to produce the answer to a question (indicating greater retrieval effort), the more likely they were to recall the answer on the final test (see also Benjamin, Bjork, & Schwartz, 1998). In a similar line of research, Auble and Franks (1978) gave subjects sentences that were initially incomprehensible (e.g., The home was small because the sun came out) and varied the amount of time before they provided a key word that made the sentences comprehensible (igloo). They found that the longer subjects puzzled over the incomprehensible sentences (making an ‘‘effort toward comprehension’’), the greater their retention of the sentences on a final test. These studies demonstrate the positive effects of retrieval effort on later retention, and the testing effect reflects another example of retrieval effort promoting retention.

Recently, Jacoby and his colleagues have obtained direct experimental evidence for different depths of retrieval in a memory-for-foils paradigm (Jacoby, Shimizu, Daniels,&Rhodes, 2005; Jacoby, Shimizu, Velanova, & Rhodes, 2005). In this type of experiment, subjects encode material under shallow or deep encoding conditions. During a first recognition test, subjects discriminate between old words that were studied under either the shallow or the deep conditions and new items (foils or lures). They are later given a second recognition test that assesses memory for the foils on the first test. For college students, having taken the first recognition test with the meaningfully studied (or deeply studied) items enhanced recognition of foils on the later test, compared with having taken the first test with the shallowly studied items. Interestingly, older adults did not show this difference (Jacoby, Shimizu, Velanova, & Rhodes, 2005), but for present purposes, the critical aspect of these studies is that manipulation of the depth of retrieval on the first test produced a large effect on recognition of the foils on the later test among younger adults.

Bjork and Bjork (1992) developed a theory to explain the testing effect and other effects of retrieval effort. They distinguished between storage strength, which reflects the relative permanence of a memory trace or permanence of learning, and retrieval strength, which reflects the momentary accessibility of a memory trace and is similar to the concept of retrieval fluency, or how easily the memory represented by the trace can be brought to mind. Their model assumes that retrieval strength is negatively correlated with increments in storage strength; that is, easy retrieval (high retrieval strength) does not enhance storage strength, whereas more effortful retrieval practice does enhance storage strength and promotes more permanent, longterm learning. However, because students often use the fluency of their current processing (retrieval strength) as evidence about the status of their current learning (e.g., see Jacoby, Bjork, & Kelly, 1994), they may elect poor study strategies. That is, students may choose strategies to maximize fluency of their current processing, even though conditions that involve nonfluent processing may be more beneficial to long-term learning. For example, students may prefer massed study (or repeated rereading) because it leads to fluent processing, although other strategies (such as spaced processing or effortful self-testing) would lead to greater long-term gains in knowledge.

We believe that the concept of transfer-appropriate processing offers an intuitive explanation for the somewhat counterintuitive testing effect, and for this reason, the concept may be useful in helping educators understand why taking tests should benefit learning—testing leads students to engage in retrieval processes that transfer in the long term to later situations and contexts. However, we note one drawback to this approach. One prediction that may be drawn from transfer-appropriate processing is that performance on a final test should be best when that test has the same format as a previous test. As we have shown, the general finding is that recall tests promote learning more than recognition tests, regardless of the final test’s format (e.g., Kang et al., in press). This result needs confirmation through additional experiments, but if it is true, it would seem to be good news for educators, because it would lead to a straightforward recommendation for educational practice. Nonetheless, the same outcome (e.g., better transfer from a short-answer test than from a multiple-choice test to a later multiple-choice test) may be construed as inconsistent with transfer-appropriate processing. However, it may not be inconsistent with the broader idea embodied in transfer-appropriate processing. If, for example, a final multiple-choice test requires effortful retrieval and a prior short-answer test fostered such effortful processes more than a prior multiple-choice test did, then it could be understandable that the prior short-answer test leads to better final performance than the prior multiple-choice test. We realize that such reasoning can quickly become circular and invulnerable to disconfirmation; the real challenge for the future is to specify how transfer-appropriate processing ideas apply to educational contexts so that they can be tested, as Thomas and McDaniel (in press) have recently done in one situation.

The testing effect cannot be explained by additional exposure to the material. This suggests that retrieval processes engaged in during a test are responsible for enhancing learning. More specifically, elaboration of encoding, more effortful or deeper encoding, and creation of different routes of access can account for the basic effect. Further, proponents of each of these ideas can point to evidence consistent with their viewpoint. The concept of transfer-appropriate processing is also congenial, albeit at a general level, to explaining the testing effect. It seems safe to say that empirical efforts to understand the testing effect have outstripped theoretical understanding, but the database is now firm enough to permit deeper understanding of the effect at a theoretical level and does permit the conclusive rejection of at least one prominent theory, that the testing effect is due to additional study, or overlearning.

Our research is influenced by the studies of Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke (2008) who explored testing effect on the example of teaching strategies (standard: STST…; repeated-study: SSST…; and repeated test:STTT…).

In our case we will also use teaching strategies. However, the teaching strategies used in the design of our program will be a little altered. The research is intended to study three teaching strategies (ST, SnT, STn) and their results in 5 minutes in order to check short-term memory and in one month so that to survey long-term memory effects.

METHOD

Our research is aimed at studying the testing-effect and its role in long-term memory. We carried out more accurate experiment devoted to sctutinization of the results received while conducting the experiment by Henry L. Roediger, III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke, 2006. Thus, in order to perform the elaborated research, fulfil suggested tasks, and to accomplish advanced hypotheses we worked out a program of research as well as conducted an experiment. Forty eight respondents divided into three groups of 16 took part in the experiment.

Participants studied material using one proposed strategy out of three possible (ST, SnT, STn).

Participants

Forty eight participants took part in the research. All respondents were students or graduates of “Ostroh Academy” National University from 17-35 of age. Fourteen men and thirty-four women comprised the total number of participants.

Participants of the experiment did not have the previous experience of learning the Swedish language. However, they had experience of learning other foreign languages. They studied Russian, English, German, Polish, and Italian.

All 48 participants were divided into three groups of 16, but they did not have a possibility to take part in the experiment at the same time. They did it simultaneously in group of two. All the participants from every group were given the same tasks, instructions, and were shown the same 30 pairs of Swedish-Ukrainian words repeated in a random order.

Materials

In this experiment we used 30 pairs of Swedish-Ukrainian words that were painstakingly chosen, checked, and standardized specially for this research.

For standardization of words a pilot survey was carried out. Twenty respondents took a part in it. The total number of participants was composed of 8 men and 12 women from 17-19 years of age.

All of the participants were the second-year students of the Economics Department at “Ostroh Academy” National University. All the participants took part in pilot survey at one and the same time, were in the same conditions, and had the previous experience of learning foreign languages. They studied Russian, English, and German.

Hence, all of the 50 pairs of words were presented to the participants twice with the 9-second interval. After this, the participators retrieved these pairs of words. They were given Ukrainian word and asked to write its Swedish equivalent. Moreover, except for this, they had a task to assess pairs of words in accordance with the following categories: familiar-unfamiliar, abstract-concrete. Words that had the utmost characteristics were turned down. After having conducted the pilot survey and standardization of words Swedish-Ukrainian pairs of words have been chosen.

The aforementioned pairs of words were displayed by E-Prime program at two computers in a random order with a 5-second interval. Also the participants were given a form to write of what foreign languages they had had previous learning experience.

Design

The participants of the experiment have been learning pairs of Swedish-Ukrainian words using one of three strategies. ST entails learning and testing all 30 pairs of words 4 times, STn involves learning all pairs of words and testing those with mistakes, SnT implies learning only the words with mistakes and testing all pairs of words (S-study, T-test). Learning and testing words was conducted four times, i.e. learning 4 times, and testing 4 times. The whole program covers 50 minutes. Five seconds were given for learning and eight – for retrieval.

In the end of the experiment the respondents were given a test to recall words learned 5 minutes or a month earlier.

Procedure

At the beginning of the experiment the respondents were given a form to write of what foreign languages they had had previous learning experience.

Next, the main procedure of the experiment was performed. All 48 participants were formed in three groups of 16. Each group has been using one of the strategies for studying material. The first group used ST strategy (S-study, T-test). The participants learned and tested in succession all pairs of words.

The participators who used SnT strategy tested all 30 pairs of words, and studied only the words in which they had made mistakes at testing. Those respondents using STn strategy learned all of words, and tested only the ones in which they had made mistakes at the previous testing. In the end of the experiment participants checked their knowledge of Swedish-Ukrainian words learned 5 minutes earlier, after completion of the experiment, and in the period of one month.

The strategies had eight stages. The first stage is learning words, the second one is testing knowledge, the third – learning words, the fourth – testing pairs of words, the fifth – learning pairs of words, the sixth – checking knowledge, the seventh – studying material, and, finally, the eighth – testing. Also in 5 minutes after the experiment was carried out the respondents were tested on knowledge of the previously learned pairs of words as well as in a month from the moment the experiment was conducted.

The respondents from every group were instructed to do their best to memorize the pairs of words. They were given 5 seconds to learn one pair of words. When time passed program automatically switched to the next word. Eight seconds were given to the participants so that to retrieve the words. When time passed, program again automatically switched to next word. Generally, the program covers 50 minutes.

The participants were given 15 seconds to retrieve words learned 5 minutes earlier and one month from the moment the experiment was performed, then program automatically shifted to the next word.

RESULTS

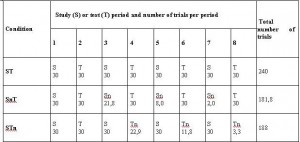

The dropout learning conditions of the present experiment differed from the standard learning condition in that, once an item was successfully recalled once on a test, it was either dropped from study periods but still tested in one condition, dropped from test periods but still repeatedly studied in a second condition, or dropped altogether from both study and test periods in a third condition (Table 1).

Table 1. Conditions used in the experiment, average number of trials within each study or test period, and total number of trials in the learning phase in each condition. SN indicates that only vocabulary pairs not recalled in the previous test period were studied in the current study period. TN indicates that only pairs not recalled in the previous test period were tested in the current test period. Students in all conditions performed a 30-s distracter task that involved verifying multiplication problems after each study period.

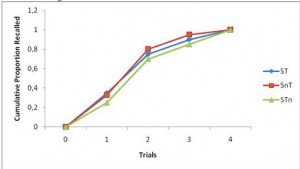

Figure 1 shows the cumulative proportion of word pairs recalled during the learning phase, which gives credit the first time a student recalled a pair. We also analyzed traditional learning curves (the proportion of the total list recalled in each test period) for the two conditions that required recall of the entire list (ST and SnT), and the results by the two measurement methods were identical. Thus, we restrict our discussion to the cumulative learning curves on which all four conditions can be compared. Figure 1 shows that performance was virtually perfect by the end of learning (i.e., all 30 English target words were recalled by nearly all subjects). More importantly, there were no differences in the learning curves of the three conditions.

Figure 1 shows the cumulative proportion of word pairs recalled during the learning phase, which gives credit the first time a student recalled a pair. We also analyzed traditional learning curves (the proportion of the total list recalled in each test period) for the two conditions that required recall of the entire list (ST and SnT), and the results by the two measurement methods were identical. Thus, we restrict our discussion to the cumulative learning curves on which all four conditions can be compared. Figure 1 shows that performance was virtually perfect by the end of learning (i.e., all 30 English target words were recalled by nearly all subjects). More importantly, there were no differences in the learning curves of the three conditions.

Fig. 1. Cumulative performance during the learning phase.

At the end of the learning phase, students in all four conditions were asked to predict how many of the 30 pairs they would recall on a final test in 1 month. They were then dismissed and returned for the final test a month later. Of key importance were the effects of the three learning conditions on the speed with which the vocabulary words were learned, on students’ predictions of their future performance, and on long-term retention assessed after a 1 month delay.

The mean number ofwords predicted to be recalled in each conditionwere as follows: ST = 18.8, SnT = 13.4, STn =22.0. An analysis of variance did not reveal significant differences among the conditions (F < 1).

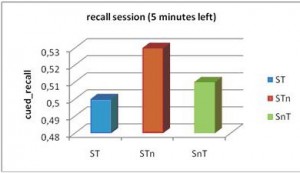

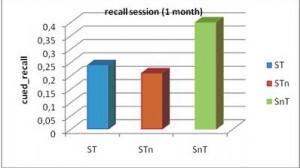

The mean proportion of idea units recalled on the final tests afterthe three retention intervals is shown in Figure 2 and 3. The cumulative recall data showed that subjects had exhausted their knowledge by the end of the retention interval and are not reported here.

Fig. 2. Mean proportion of idea units recalled on the final test after a 5-min retention interval as a function of learning condition.

Fig. 2. Mean proportion of idea units recalled on the final test after a 5-min retention interval as a function of learning condition.

Fig. 3. Mean proportion of idea units recalled on the final test after a 1-month retention interval as a function of learning condition.

Fig. 3. Mean proportion of idea units recalled on the final test after a 1-month retention interval as a function of learning condition.

The results were submitted to a 2×3 analysis of variance (ANOVA), with learning condition (restudying or testing) and retention interval (5 min, or 1 month) as independent variables. This analysis revealed a main effect of testing versus restudying, F(1, 117)536.39, Zp 2 5.24, which indicated that, overall, initial testing produced better final recall than additional studying. Also, the analysis revealed a main effect of retention interval, F(2, 117) 5 50.34, Zp 2 5 .46, which indicated that forgetting occurred as the retention interval grew longer. However, these main effects were qualified by a significant Learning Condition _ Retention Interval interaction, F(2, 117) 5 32.10, Zp 2 5 .35, indicating that restudying produced better performance on the 5-min test, but testing produced better performance on 1-month tests.

DISCUSSION

Our experiment also speaks to an old debate in the science of memory, concerning the relation between speed of learning and rate of forgetting . Our study shows that the forgetting rate for information is not necessarily determined by speed of learning but, instead, is greatly determined by the type of practice involved. Even though the four conditions in the experiment produced equivalent learning curves, repeated recall slowed forgetting relative to recalling each word pair just one time.

Importantly, students exhibited no awareness of the mnemonic effects of retrieval practice, as evidenced by the fact that they did not predict they would recall more if they had repeatedly recalled the list of vocabulary words than if they only recalled each word one time. Indeed, questionnaires asking students to report on the strategies they use to study for exams in education also indicate that practicing recall (or self-testing) is a seldom-used strategy. If students do test themselves while studying, they likely do it to assess what they have or have not learned, rather than to enhance their long-term retention by practicing retrieval. In fact, the conventional wisdom shared among students and educators is that if information can be recalled from memory, it has been learned and can be dropped from further practice, so students can focus their effort on other material. Research on students’ use of self-testing as a learning strategy shows that students do tend to drop facts from further practice once they can recall them. However, the present research shows that the conventional wisdom existing in education and expressed in many study guides is wrong. Even after items can be recalled from memory, eliminating those items from repeated retrieval practice greatly reduces long-term retention. Repeated retrieval induced through testing (and not repeated encoding during additional study) produces large positive effects on long-term retention.

REFERENCES

- Bjork, R.A. (1975). Retrieval as a memory modifier: An interpretation of negative recency and related phenomena. In R.L. Solso (Ed.), Information processing and cognition: The Loyola symposium (pp. 123–144). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bjork, R.A. (1988). Retrieval practice and the maintenance of knowledge. In M.M. Gruneberg, P.E. Morris, & R.N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory: Current research and issues (Vol. 1, pp. 396–401). New York: Wiley.

- Bjork, R.A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gates, A.I. (1917). Recitation as a factor in memorizing. Archives of Psychology, 6(40).

- Glover, J.A. (1989). The ‘‘testing’’ phenomenon: Not gone but nearly forgotten. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 392–399.

- Hogan, R.M.,&Kintsch,W. (1971). Differential effects of study and test trials on long-term recognition and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 10, 562–567.

- Izawa, C. (1967). Function of test trials in paired-associate learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 75, 194–209.

- Rawson, K.A., & Kintsch,W. (2005). Rereading effects depend on time of test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 70–80.

- Roediger, H.L., III. (1990). Implicit memory: Retention without remembering. American Psychologist, 45, 1043–1056.

- Roediger, H.L., III, Gallo, D.A., & Geraci, L. (2002). Processing approaches to cognition: The impetus from the levels-of-processing framework. Memory, 10, 319–332.

- Roediger, H.L., III, & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). The power of testing memory: Implications for educational practice. Unpublished manuscript, Washington University in St. Louis.

- Roediger, H.L., III, & Thorpe, L.A. (1978). The role of recall time in producing hypermnesia. Memory & Cognition, 6, 296–305.

- Spitzer, H.F. (1939). Studies in retention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 30, 641–656.

- Thompson, C.P., Wenger, S.K., & Bartling, C.A. (1978). How recall facilitates subsequent recall: A reappraisal. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4, 210–221.

- Tulving, E. (1967). The effects of presentation and recall of material in free-recall learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6, 175–184.

- Wheeler, M.A., & Roediger, H.L., III. (1992). Disparate effects of repeated testing: Reconciling Ballard’s (1913) and Bartlett’s (1932) results. Psychological Science, 3, 240–245.